Partnering with Nature’s Microbial Guardians

A Look at Chris Trump’s Indigenous Predatory Microorganisms Approach

In the world of natural farming, there’s a quiet revolution happening — one that doesn’t rely on chemicals, but on life itself.

IPMO, short for Indigenous Predatory Microorganisms, is a method shared by natural farming educator Chris Trump that taps into nature’s built-in system for regulating pests.

It’s based on a simple idea: in every healthy ecosystem, there are already countless microorganisms that keep insect populations in balance. Rather than importing lab strains or synthetic sprays, IPMO focuses on cultivating and multiplying the predatory microbes that already thrive in your local environment — the ones that have co-evolved with the same pests you face on your farm or in your garden.

What IPMO Really Is

When people hear “microorganisms,” they often think of soil bacteria or compost fungi — the decomposers. But IPMO works with a different set of life forms: entomopathogenic organisms.

These are naturally occurring fungi and bacteria that infect and kill insects, breaking down their bodies and releasing nutrients back into the soil.

If you’ve ever turned over a leaf and seen a mummified insect dusted with white or green fuzz, you’ve already seen IPMO in action. That fuzz is the sporulating form of fungi like Beauveria bassiana or Metarhizium anisopliae — both classic examples of nature’s pest regulators.

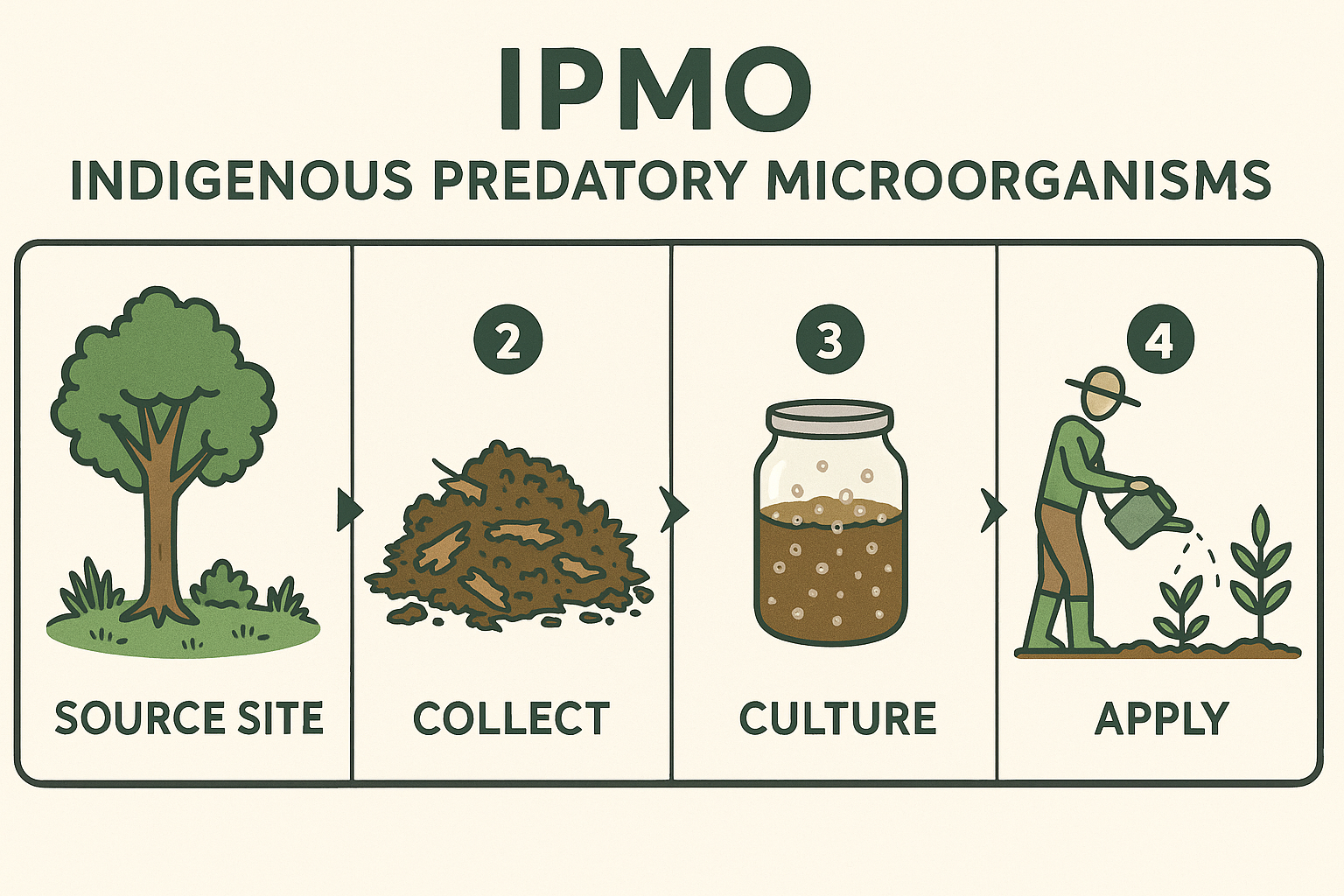

The Collection Phase: Learning from the Forest

To create IPMO, natural farmers start by observing nature. They look for insects in their area that have already been infected by these beneficial fungi — usually found in shaded, humid places like forest floors, mulch, or under leaves.

These naturally infected insects are then collected and used as a biological “starter culture.”

They contain the indigenous fungal and bacterial species that are perfectly adapted to the local environment.

The Culturing Step: Life Amplified

Next, those infected insects are introduced to a culture — often something simple and natural, such as cooked white rice.

This acts as both food and habitat, allowing the fungi to spread from the insect bodies into the rice substrate.

Over several days, the mixture becomes a living culture, visibly colonized by the same beneficial fungi that were present on the original insects.

At this point, you’ve effectively amplified your region’s own predatory microorganisms in a safe, contained medium.

From Culture to Field

Once the rice substrate is fully colonized, farmers typically move the culture into a liquid stage in a larger vat, where it is allowed to culture the fungi before being applied in diluted form to fields or gardens.

This step transforms the solid culture into a liquid microbial solution that can be distributed over larger areas, helping reintroduce those beneficial organisms into the farm ecosystem.

The exact ratios, timing, and conditions for this stage require training and precision — which is why natural farming practitioners often study directly under teachers like Chris Trump before attempting large-scale production.

Why It Matters

The beauty of IPMO lies in its philosophy: nature already has the answers.

Instead of trying to dominate pests, we can work with the same life forms that have kept ecosystems in balance for millennia.

Using IPMO:

- Reduces reliance on synthetic pesticides.

- Encourages long-term soil and plant health.

- Builds a living resilience into the farm ecosystem.

- Reconnects the farmer with the natural intelligence of their land.

It’s not a quick fix — it’s a way of thinking. A partnership with the unseen world beneath our feet and around our crops.

Closing Thoughts

IPMO reminds us that sustainable agriculture doesn’t come from new inventions, but from remembering how nature already works.

Through observation, patience, and respect for microbial life, farmers can build systems that heal themselves, protect their crops, and nurture balance from within.

As Chris Trump often says, “We’re not making nature better — we’re just learning to listen.”